The Tighten Test: 12 Steps to a Better Team

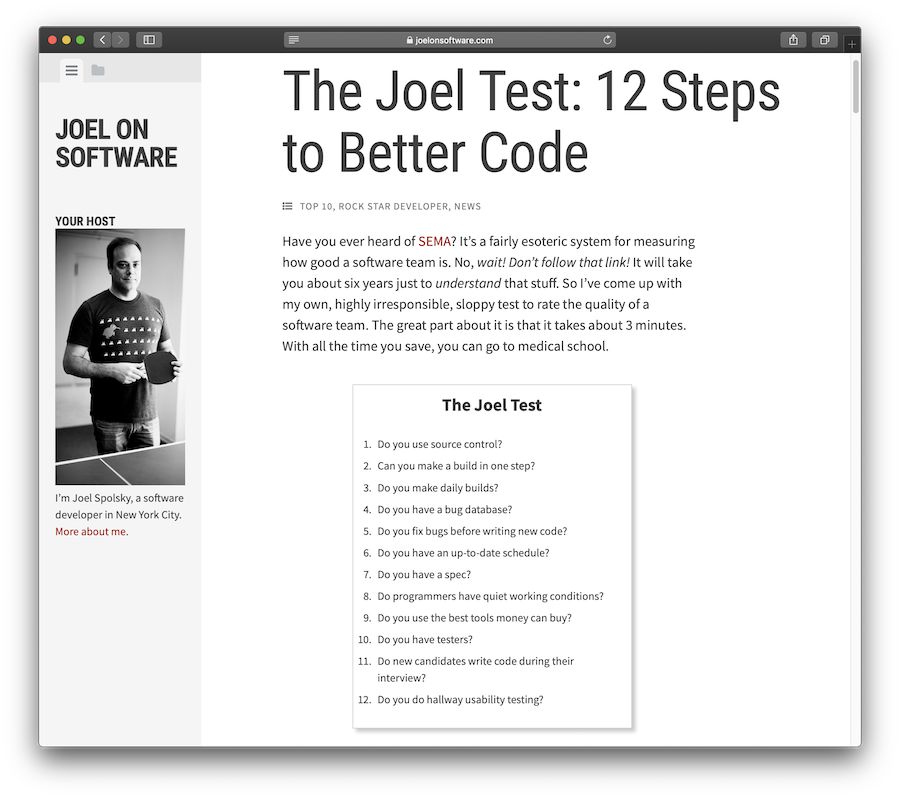

Twenty years ago today, Joel Spolsky (who later co-founded Stack Overflow) published The Joel Test: 12 Steps to Better Code listing 12 metrics for rating the quality of a software development team. The premise is simple: you get 1 point for each “yes” answer, for a total score of up to 12 points.

It’s presented a bit tongue-in-cheek: he freely acknowledges it as “sloppy” and even “highly irresponsible”. But the list resonated with so many software developers that it’s still commonly in use today. Many job posts still include their “Joel Score” as a signal to developers that they care about the health and quality of their team.

Here at Tighten, we regularly discuss (and publish) our opinions about what makes a good software team, and how to maximize our own team’s health, productivity, and happiness. So we thought it would be fun to celebrate the 20 year anniversary of this iconic post with our own twist on it—heavily opinionated, based on our shared values, and sourced from our experience as web and app developers who regularly work with a variety of different software organizations.

The Tighten Test

- Do you work 40 hours a week or less?

- Do you set aside time at work for learning?

- Do you have the tools you need to get the job done?

- Do you keep an up-to-date list of prioritized tasks/tickets?

- When new features take longer than expected, do you cut their scope and/or extend the timeline?

- Do your codebases have up-to-date written setup and deployment instructions?

- Do you write great commit messages and pull requests?

- Is all incoming code automatically linted and tested?

- Is all incoming code reviewed by someone who didn’t write it (or written while pairing)?

- Do your local and staging environments match production as closely as possible?

- Are you automatically notified about errors in production?

- Do you deploy to production at least once a week?

As with the original test, 12/12 is a perfect score, 11 is tolerable, but 10 or lower and you’ll start noticing problems. Joel also noted that most software organizations are running with a score of 2 or 3.

1. Do you work 40 hours a week or less?

This one should be self-explanatory: the easiest way to ensure people are happy is to give them time to enjoy their life and maintain their health. There are many studies about the negative effects on health caused by overworking, and employees who are healthy tend to be happier and more productive. Some companies like Microsoft have even been experimenting with four-day workweeks in recent years—and seeing boosts in productivity.

At Tighten we don’t have a four-day workweek (yet? 😉), but we’ve been taking 20% time on Fridays since 2016: more on this in the next section. We also don’t work overtime.

2. Do you set aside time at work for learning?

It’s one thing to be a good developer, but to stay a good developer you have to constantly learn new things and also keep your existing skills sharp. While it’s impossible to learn everything, the best software development teams make some space for learning at work.

As mentioned, at Tighten we dedicate a day every week to learning and teaching: on Fridays we contribute to open source, read or watch tutorials, write blog posts, etc., instead of our usual client work. But you don’t need to set aside an entire day—there are other ways to make space for learning, like encouraging pair programming to spread knowledge around, including time for research in your tasks, and arranging internal talks within your team.

3. Do you have the tools you need to get the job done?

If someone on your team needs a license for something, can they get it? If you need specific office equipment—like an ergonomic desk or keyboard—will your company provide it for you?

Some developers manage to produce amazing work on old, slow laptops—or even a paper and pencil—but if your company’s business depends on your software, everyone on your team needs hardware that won’t slow them down, software to make them more productive, an office setup that maximizes their physical well-being, and space to take care of their mental health.

4. Do you keep an up-to-date list of prioritized tasks/tickets?

Joel’s original test included “Do you have a bug database?”, but we wanted to stress the importance of regularly prioritizing tickets at the top of your list. Working on the right thing is more important than doing good work on the wrong thing, so make sure your team is regularly re-ordering tickets so developers are always picking up the highest priority task.

5. When new features take longer than expected, do you cut their scope and/or extend the timeline?

In our experience, setting deadlines based on estimates doesn’t work, since estimates are merely a guess at what might happen in the future; not only is software complex and unpredictable, but requirements and priorities change all the time. Deadlines also tend to be the primary cause of overtime; many teams “crunch” to hit a due date, which can jeopardize team members’ physical & mental health.

Instead of estimating and pretending to know the future, we just do our best work every day and keep in close communication with our clients so everyone always knows the status of the project. If a client has a target to hit, we work with them to cut the scope of the requested feature—fans of agile practices will be familiar with this tactic—to ensure a usable, simpler version of what they need will be done with time to spare. If there’s time left later, you can always go back and add more to a feature.

Cutting scope allows us ship to production early and often, get feedback on features from real users faster, and save a lot of time by not developing and maintaining complex additions when users end up needing something different than expected.

6. Do your codebases have up-to-date written setup and deployment instructions?

How long does it take a new developer to get set up with your codebase? Without written instructions, it might take anywhere from a few days to a few weeks.

Since we work with a variety of clients, we’re constantly the new developers on a project—and while not having written instructions doesn’t necessarily mean your code is bad, we find that well-documented codebases are a good indication of regular maintenance and care for the project. Written instructions also help your team internally: for example, they can make a huge difference if the only person who knows how to deploy leaves the company.

7. Do you write great commit messages and pull requests?

While Git history might not be as important on solo projects, it matters a lot on a team. As frequent newcomers to a project, commit messages are invaluable in helping us understand why changes were made and how they relate to each other, without needing years of context or domain knowledge.

Understanding existing code is often the most time-consuming part of a development task. Once someone on a team wraps their brain around a programming challenge, it would be silly to have other developers spend that time again when they review or change the same code—but that’s exactly what happens when you leave commit messages and PR descriptions blank. The moment you submit a PR, you have more context about the task you’re working on than anyone else, so write it down while you remember! This will save time for everyone else: people who review your PR, new developers in the future who dig through Git history, and even future you when you can’t remember the details.

Great pull requests should also be digestible: ideally containing visual demonstrations, and small enough to be reviewable in 30 minutes or less. Since PR reviewers don’t have as much context as the developer who worked on a task, reviewing a huge PR can be disproportionately time-consuming.

8. Is all incoming code automatically linted and tested?

Disagreements about code style happen on every development team, but that’s no reason to let them get in the way of getting work done. Pick a style (preferably the standard in whatever language you’re using) and use linter and/or fixer tools to enforce it automatically, and never waste time arguing about code style again. You can fix your entire codebase in one go and ignore the commit in Git blame to maintain a useful history. As an added benefit, all future code changes will be easier to review since your diffs won’t be cluttered with meaningless changes to code style.

Running automated tests against all new code is also essential. Existing tests make sure new code hasn’t broken anything, and new tests protect new code from breaking in the future. The amount of code covered by tests matters too: most of it should be covered (though 100% coverage is often more trouble than it’s worth). Running an automated test suite with one test is better than nothing, but ultimately not enough to give you confidence that your app still works.

9. Is all incoming code reviewed by someone who didn’t write it (or written while pairing)?

One way we ensure that our code is of the highest quality possible is by always having a fresh set of eyes look it over before we consider it “done”.

Whenever possible we work in two-person teams, with each developer reviewing the other’s PRs on GitHub before they’re merged. We also have a strong pair programming culture here, where two developers will work together on the same code simultaneously while sharing screens over Zoom or some other tool.

Particularly when building large or complex features, pair programming often results in superior code compared to code that was written solo—not only because it helps weed out errors before they make it into a commit, but also because pairing allows the developers to reason through design decisions together in real-time, in a deeper and more meaningful way than is possible during a conventional code review. Plus, pairing can be a ton of fun, and is a great way to learn from one another!

Either way, whether through pairing or a GitHub-based code review of a PR—when it comes to code quality, four eyes are always better than two.

10. Do your local and staging environments match production as closely as possible?

Developing on different framework, language, database, or operating system versions will almost certainly cause unnecessary friction (“It works on my machine!”). Limiting the differences between environments also limits time wasted on errors caused by mismatched software versions. If you use build scripts and dependency managers (like Composer), you can update dependencies automatically in all environments, and take advantage of new language or software features everywhere.

Using tools like Docker, you can go even further and have your environments match exactly. If your local, staging, and production environments are identical, developers can prepare the application for the exact environment in which it will run. And with continuous integration and deployment (CI/CD), updates to the project and environment can be built, tested, and shipped the same way.

11. Are you automatically notified about errors in production?

Nobody writes bug-free code, and you can’t fix errors you don’t know about. Make sure any errors that occur in production are reported somewhere the whole team can see. Many legacy PHP apps silence errors altogether, which is even worse—silencing an error doesn’t make it go away! There are plenty of bug reporting services like Bugsnag and Sentry that give you a full stack trace, request & session data, and all the context you’ll need to fix most errors, as well as configurable notification channels like Slack.

12. Do you deploy to production at least once a week?

The timeframe is arbitrary; the important thing here is that you’re deploying to production frequently. Deploying shouldn’t be a big, scary event: if you do it often enough, if your deployments happen automatically after tests pass, and if you report errors in production there’s really not much to worry about. Modern continuous integration (CI) pipelines make it easier than ever to deploy automatically. We use tools like GitHub Actions and Laravel Envoyer to deploy to production every time we push code and our tests pass.

If you don’t meet all of these guidelines today, don’t worry! They simply serve as a set of goals our team has agreed to work toward, because they make us happier and more productive developers. We hope they’ll do the same for you.

Thanks to @dhicking for the original half-baked idea behind this post, and @jakebathman, @keithdamiani, and @marcusamoore for contributing content & reviewing.

in your inbox:

let’s talk.

Thank you!

We appreciate your interest.

We will get right back to you.