Introduction to Delegated Types

Back in 2024, the 37signals folks released Writebook, another cool product under their ONCE line of products. Writebook ("the easiest way on earth to publish a book online") features one of my favorite patterns: Delegated Types, which is a way to represent class hierarchies in Active Record ORMs. Think of it like "Dog extends Animal", but without using inheritance.

They recently started talking more about it on their company blog. In this post, we'll explore what Delegated Types look like, discuss their benefits, compare them to other ways of representing hierarchies like Single-Table Inheritance (STI), and explore a few interesting use cases they enable.

Introduction

There are a couple of ways to represent hierarchies in Active Record ORMs like Eloquent. The most common one is Single-Table Inheritance (STI), which stores all subtype attributes in a single database table. This pattern suits hierarchies where subtypes share similar data, but implement different behavior.

As an example of that, we'll recreate some models for a chat application based on 37signals' first ONCE product: Campfire. In Campfire, we have a Room model which represents a chat room. Rooms can be open, closed, or direct. They used STI to represent the different types of rooms:

use Illuminate\Database\Eloquent\Model;

use Parental\HasChildren;

use Parental\HasParent;

class Room extends Model

{

use HasChildren;

public function members() { /* ... */ }

public function creator() { /* ... */ }

}

class Closed extends Room

{

use HasParent;

}

class Open extends Room

{

use HasParent;

public static function booted()

{

static::saved(function (Open $room) {

$room->ensureAllUsersHaveAccess();

});

}

public function ensureAllUsersHaveAccess(): void

{ /* ... */ }

}

For the sake of brevity, we only have open and closed rooms here. STI isn't supported in Eloquent natively, but we can use it by installing the Parental package via Composer:

composer require tightenco/parental

In this example, there's no difference between the subtypes of room. It all fits in a single database table:

rooms

id

user_id # creator

name

type # STI

Parental uses that type attribute to determine which class will be instantiated at runtime based on its value.

One example of different behavior here is in the model callbacks. When an open room is saved, the ensureAllUsersHaveAccess() method is called. This is useful because, in Campfire, rooms may change type within their life cycle. A closed could open later on, which would trigger the callback and grant everyone access to it. Closed rooms, on the other hand, should only grant access to users who received explicit access.

STI may get complicated fast when each subtype needs different data. We end up with lots of nullables in our database table (or worse, schema-less JSON fields).

The answer to this limitation was here all along: polymorphic relationships. Adam Wathan, Tighten Alumnus and creator of Tailwind CSS, explored this technique back in 2015 with his "Pushing Polymorphism to the Database" approach. Now, years later, we finally have a proper name for it: Delegated Types!

Delegated Types

The pattern was documented in this PR to Rails, and it seems to have been an extraction of the HEY codebase.

Delegated Types works on top of Polymorphic Relationships, but it upends it. I'll show you what I mean. Let's imagine our application has both a Video and a Post model. Both are able to receive Comments. We might be used to seeing the most basic examples of polymorphic relationships:

class Comment extends Model

{

public function commentable(): MorphTo

{

return $this->morphTo();

}

}

trait Commentable

{

public function comments(): MorphMany

{

return $this->morphMany(Comment::class, 'commentable');

}

}

class Post extends Model

{

use Commentable;

}

class Video extends Model

{

use Commentable;

}

With polymorphic relationships, we define horizontal hierarchies instead of the traditional vertical hierarchies we're used to. Notice how it's almost like there's an invisible hierarchy here; we even have a name for it: Commentable. Both Post and Video are part of this invisible hierarchy. The database structure here would look something like this:

videos

id

source_path

# ...

posts

id

title

content

# ...

comments

id

commentable_id # related model ID

commentable_type # related model TYPE

content

# ...

Polymorphic relationships need a pair of columns (id and type) to work, so they can store references to different database tables.

Although there are cases where regular polymorphic relationships (like the one above) are enough, with Delegated Types we get to explicitly model the hierarchy. And, even better, we can rely on delegation instead of inheritance to do so.

Here's an example of how it works. We're creating an entity between our commentable types and the comments, which we're calling Entry. The entryable() MorphTo relationship defines a one-to-one polymorphic relationship, allowing an Entry to be attached to any other type:

class Entry extends Model

{

public function entryable(): MorphTo

{

return $this->morphTo();

}

}

trait Entryable

{

public function entry(): MorphOne

{

return $this->morphOne(Entry::class, 'entryable');

}

}

class Post extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

class Video extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

By structuring our domain models this way, we get a shared entity between all the records in our hierarchy. Our database structure would now look like this:

entries

id

entryable_id # related model ID

entryable_type # related model TYPE

# ...

videos

id

source_path

# ...

posts

id

title

content

# ...

This way, we can ensure all Videos and Posts have a related Entry model. Since all models are Entryables, we now have a shared place to attach common behavior to. This means that instead of making our Comment model polymorphic, we can now attach it to the Entry model and have it as a simple has many/belongs to pair of relationships:

class Entry extends Model

{

public function entryable() { /** ... */ }

public function comments(): HasMany

{

return $this->hasMany(Comment::class);

}

}

class Comment extends Model

{

public function entry(): BelongsTo

{

return $this->belongsTo(Entry::class);

}

}

If we needed to get the comments of a Video, for instance, we'd go through the related Entry instead. Our database structure would now look something like this:

entries

id

entryable_id # related model ID

entryable_type # related model TYPE

# ...

videos

id

source_path

# ...

posts

id

title

content

# ...

comments

id

entry_id

content

# ...

This change in design enables new use cases and makes the app a lot more flexible. Now, we can easily add shared behavior across all our Entryable models, represent richer hierarchies, and (perhaps my favorite of all) make our data "immutable." We'll explore each of these use cases next.

1. Shared Behavior

With the regular polymorphic approach, commenting was a shared behavior between all entries. So how do we implement this? Let's think in terms of REST here:

POST /posts/{post}/comments

POST /videos/{video}/comments

POST /comments/{comment}/comments

...

This is not a big problem if comments was the only shared behavior in our system. But as soon as we start adding more of these, we can sense the smell:

POST /posts/{post}/comments

POST /videos/{video}/comments

POST /comments/{comment}/comments

...

POST /posts/{post}/likes

POST /videos/{video}/likes

POST /comments/{comment}/likes

...

POST /posts/{post}/reactions

POST /videos/{video}/reactions

POST /comments/{comment}/reactions

...

This way, routes (and controllers!) proliferate very quickly. Now, let's compare this with the Delegated Types version. Since all relevant entries in our application are part of the same abstraction with a root Entry model associated with them, and the Commentable behavior was simplified to a hasMany/belongsTo relationship on the Entry, our routes and controllers can be simplified:

POST /entries/{entry}/comments

POST /entries/{entry}/likes

POST /entries/{entry}/reactions

...

We now have a single route and controller for creating comments:

class EntryCommentsController

{

public function store(Request $request, Entry $entry)

{

$comment = $entry->comments()->create($request->validate([

'content' => ['required', 'max:255'],

]));

return back()->withFragment(sprintf(

'#%s',

dom_id($comment),

));

}

}

If, for some reason, you want to disable this shared behavior for specific Entryables, we may do so via delegation:

class EntryCommentsController

{

public function store(Request $request, Entry $entry)

{

$this->authorize($entry, 'addComment');

// ...

}

}

class EntryPolicy

{

public function addComment(User $_user, Entry $entry): bool

{

return $entry->entryable->canHaveComments();

}

}

trait Entryable

{

// ...

public function canHaveComments(): bool

{

return true;

}

}

class Video extends Model

{

use Entryable;

public function canHaveComments(): bool

{

return $this->allow_comments;

}

}

In this example, we're disabling comments on a video if it has the allow_comments flag turned off. This flag would be stored in the videos table, not in the entries one. In other words, we're delegating to the Entryable, where we can override the behavior if we want to. Of course, this is just an example, and if being able to disable comments is something shared between all Entryables, that data could be moved to the Entry model's table instead.

We can add shared behavior across the system more easily now. For instance, if we were building a Reactions feature, we could do that in the Entry and enable that across the board for all our Entryable resources. Another example would be a "remind me later" feature, which could also be done at the Entry resource level, and so on.

2. Richer Hierarchies

When using Active Record, we're used to thinking in terms of relational databases, such as "A Post has Many Comments." That's good and simple, and we all like simple. But, sometimes, the Real World™ is more complicated than that. What if a Post has many client-facing comments but also internal notes that should all be listed in the same feed for some users? Or what if a comment also has comments, like threads?

With Delegated Types, we can make the Entry model recursive by adding a nullable parent_id attribute to it! This way, we can represent more complicated hierarchies. For instance, we can turn our Comment model into an Entryable too:

class Entry extends Model

{

public function entryable(): MorphTo

{

return $this->morphTo();

}

public function parent(): BelongsTo

{

return $this->belongsTo(Entry::class);

}

public function children(): HasMany

{

return $this->hasMany(Entry::class, 'parent_id');

}

}

trait Entryable

{

public function entry(): MorphOne

{

return $this->morphOne(Entry::class, 'entryable');

}

}

class Post extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

class Video extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

class Comment extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

Our database structure now looks like this:

entries

id

entryable_id # related model ID

entryable_type # related model TYPE

parent_id # parent entry reference (nullable)

# ...

videos

id

source_path

# ...

posts

id

title

content

# ...

comments

id

content

# ...

This enables a new set of interactions that give us more flexibility on how our models are nested. For instance, we can allow comments on anything (even other comments), and we can have a mix of different types of Entryables as children of the same Entry at the same hierarchy level. I know, it sounds complicated, but let me show you what I mean.

In email applications, for example, we can group messages on different folders/mailboxes. In HEY, they call the model that represents that concept a Box, and we can have a few pre-defined records for it: Imbox (not a typo), Feed, Papertrail, etc.

Email messages and replies of the same message are also grouped, forming a single thread of email messages. In HEY, they seem to call the thread of messages a Topic (I'm guessing here based on the URL, which is something like https://app.hey.com/topics/123123 and shows all emails of that thread).

Messages are not the only model nested within a Topic in Hey, though. A business account may have more people handling the same email account. To help the team coordinating a reply to a given message, they can leave private notes to each other. Differently than email messages, which are sent to all the email recipients of the thread, private notes are only for internal use, they never leave the app as an email, and only team members of the business account can see them.

These notes are listed side-by-side with the actual email messages on the same topic. Here's what they look like from a marketing image I got from their Play Store (you can see the private notes have a blue background in the image):

If we were building that with Delegated Types, our database structure could look like this:

boxes

id

name

# ...

entries

id

box_id # the box which this entry belongs to

entryable_id # related model ID

entryable_type # related model TYPE

parent_id # the parent entry (nullable)

# ...

topics

id

name # the subject heading

# ...

messages

id

subject

content

# ...

notes

id

content

# ...

Notice that our hierarchy is mainly implemented in the Entry model, leaving our actual domain models thin—they only care about their actual data attributes and nothing else. Then, our Eloquent models would look like this:

class Box extends Model

{

public function entries(): HasMany

{

return $this->hasMany(Entry::class);

}

public function topics(): HasMany

{

return $this->entries()->topics();

}

}

class Entry extends Model

{

#[Scope]

public function topics(Builder $query): void

{

$query->where('entryable_type', (new Topic)->getMorphClass());

}

public function box(): BelongsTo

{

return $this->belongsTo(Box::class);

}

public function entryable(): MorphTo

{

return $this->morphTo();

}

public function parent(): BelongsTo

{

return $this->belongsTo(Entry::class);

}

public function children(): HasMany

{

return $this->hasMany(Entry::class, 'parent_id');

}

}

trait Entryable

{

public function entry(): MorphOne

{

return $this->morphOne(Entry::class, 'entryable');

}

}

class Topic extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

class Message extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

class Note extends Model

{

use Entryable;

}

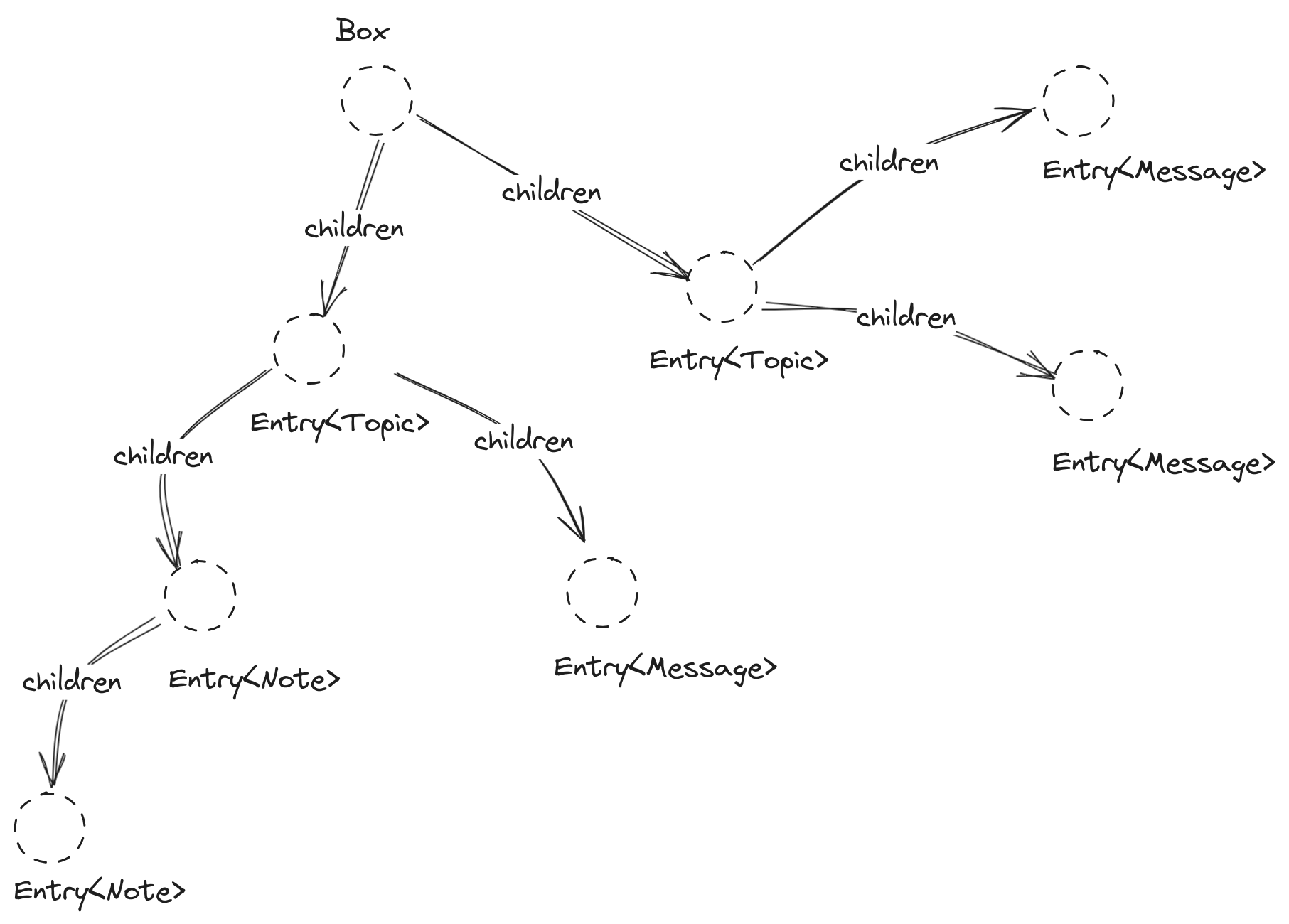

The Box model here works as a "bucket of entries". All entries would belong to a single Box, no matter how deep in the hierarchy it would be. In the app, we could enforce that Topics are always the first level of entries in a box. And, inside of a Topic, we could have Message and Note entries.

We could add affordances to help navigate this graph. For example, our topics relation in the Box model could filter only entries where the Entryable is a Topic:

$box->topics # [Entry<Topic>, Entry<Topic>, ...]

$box->entries # [Entry<Topic>, Entry<Message>, Entry<Note>, Entry<Topic>, ...]

And, since Entries are recursive (meaning we can nest entries on them), we can list all the messages and notes inside of a Topic using its Entry's children relationship:

$topic->entry->children # [Entry<Message>, Entry<Note>, ...]

This way, we can build much richer features. We'd only have to make sure Entries are created the same way. For instance, when we're creating Notes on a Topic, the URL would be something like:

POST /topics/{topic}/notes

But what we'd pass to it would be the ID of the Topic's Entry instead of the Topic's ID:

<form action="{{ route('topics.notes.store', ['topic' => $topic->entry]) }}" method="post">

<!-- ... -->

</form>

Then, in our TopicNotesController@store action, we'd type-hint the Entry model for the $topic resource so the route model-binding works as we expect. Then, we'd create a new Entry for the Note that, once created, would be associated with the root Box instance. We can get that from the Topic's Entry::box() relationship:

class TopicNotesController

{

use AuthorizesRequests;

public function store(Request $request, Entry $topic)

{

$this->authorize($topic, 'addNotes');

$topic->box->createEntry(

entryable: $this->makeNote($request),

parent: $topic,

);

return back(fallback: route('topics.show', $topic))

->with('notice', __('Note created.'));

}

private function makeNote(Request $request): Note

{

return Note::make($request->validate([

'body' => ['required'],

]));

}

}

class Box extends Model

{

// ...

public function createEntry(Model $entryable, ?Entry $parent = null): Entry

{

return DB::transaction(function () use ($entryable, $parent) {

return $this->entries()->create([

'entryable' => tap($entryable)->saveOrFail(),

'parent' => $parent,

]);

});

}

}

Notice that in the store() action method, we're type-hinting the Entry model, but our variable is called $topic. That's because, in this example, I still wanted to name the resource "topics", the routing would be defined as:

Route::resource('topics.notes', TopicNotesController::class)

->only(['store']);

Which would result in a route like:

POST /topics/{topic}/notes name: topics.notes.store

On a side note, you may have noticed we're passing the entryable and parent relationships here as if they were attributes on the model. I wish this was native in Laravel, but it's not (at least at the time of this writing). However, we can achieve it with mutators:

class Entry extends Model

{

protected $fillable = [

// ...

'entryable',

'parent',

];

// ...

public function setEntryableAttribute($entryable): void

{

$this->entryable()->associate($entryable);

}

public function setParentAttribute($parent): void

{

$this->parent()->associate($parent);

}

}

Well, just a tangent here. Let's get back to Delegated Types.

In Basecamp, their rich hierarchies seem to be turned up to 11. Pretty much anything inside a Project is a Recording (their Entry model). And there also seems to be this exact same kind of recursiveness going on. Check out their post on recordings to learn more about this.

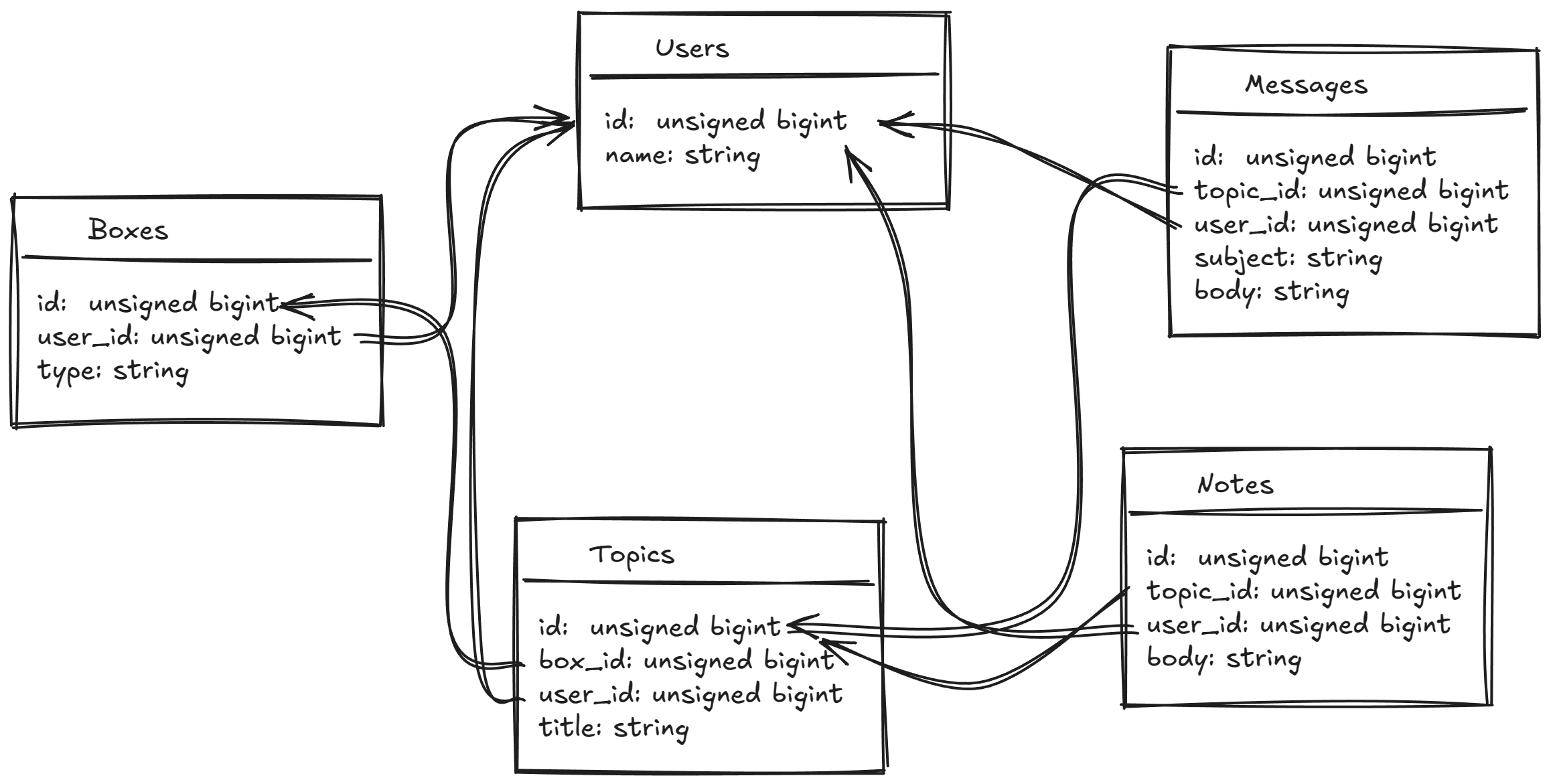

In our example, our database schema went from something that looked like this:

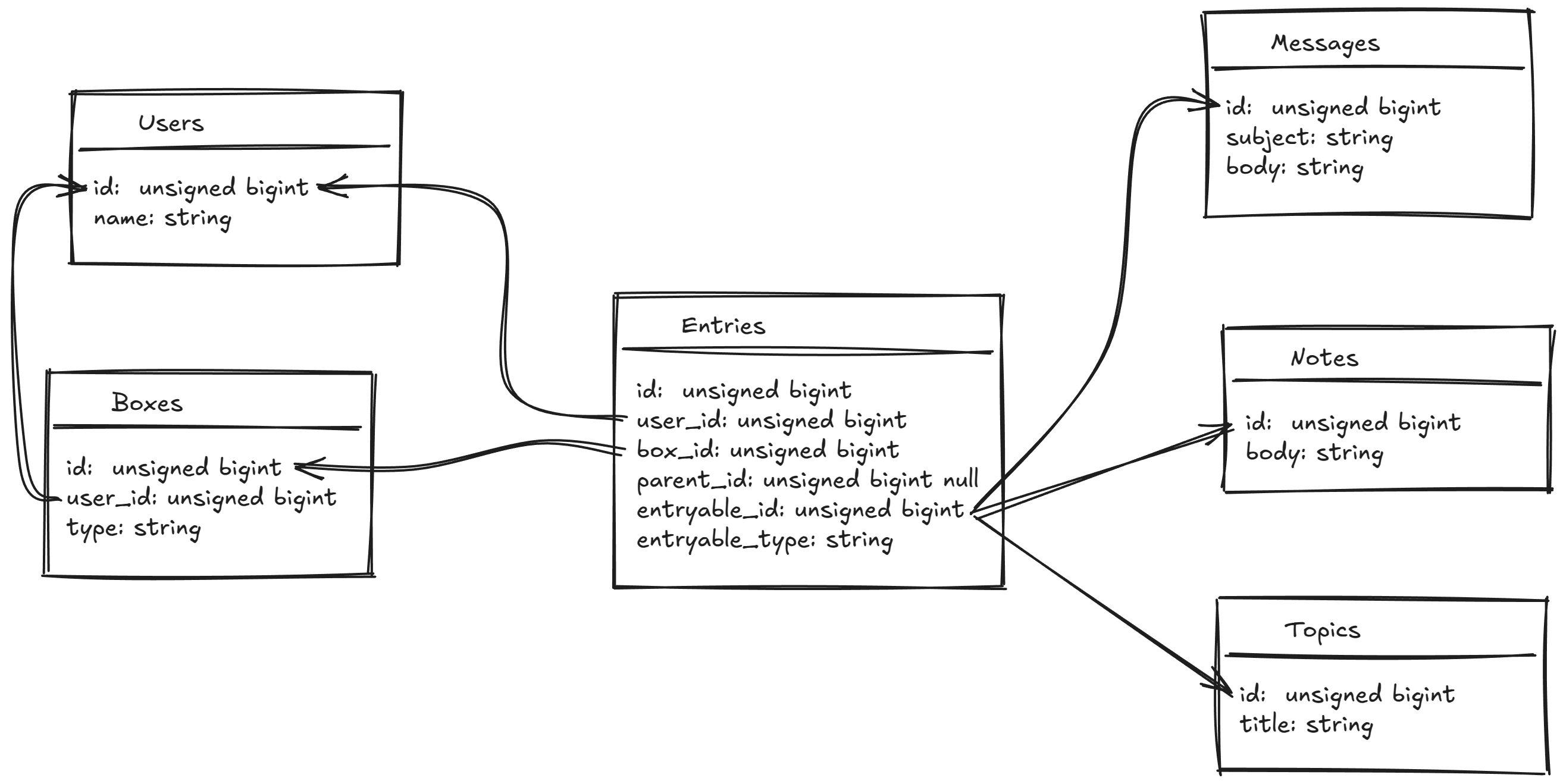

... into something that looks like this:

We're essentially treating our relational database as if it were a graph:

As with everything in software, there are trade-offs: things are a bit more abstract than before. However, the flexibility this provides is helpful. Especially when it comes to the next two topics.

3. Immutability and History

In the talk "The Value of Values", Rich Hickey (the creator of Clojure) talks about how we're building information systems that only care about the "current state" of things. He calls it "place-oriented". He claims that information systems must be able to retain historical information about all the previous states to be useful.

This is often where folks turn to Event Sourcing. But Delegated Types can help here as well. To be able to retain past information, we only need a few things:

- To turn our "Edits" into first-class citizens in our system

- To only ever expose the Entry IDs, and never the underlying Entryable resource ID (we already saw instances of this in previous examples)

With these two constraints in place, we could treat our Entry model as a pointer to the current state of the Entryable it represents. This way, instead of updating the Entryable model's state, we could create a new one and update the Entry's reference of the current Entryable to point to the new record!

For this example, let's continue with the mailbox example we worked on in the previous section. Here's what the TopicNotesController@update action could look like:

class TopicNotesController

{

// ...

public function update(Request $request, Entry $note)

{

$this->authorize('update', $note);

$note->edit(entryable: $this->makeNote($request));

return to_route('topics.show', $note->parent);

}

}

class Entry extends Model

{

use Editable;

// ...

}

trait Editable

{

public function edits(): HasMany

{

return $this->hasMany(Edit::class);

}

public function edit(Model $entryable, ?User $user = null): static

{

$user ??= auth()->user();

return DB::transaction(function ($entryable, $user) {

$this->edits()->create([

'entryable' => $this->entryable,

'user' => $user,

]);

$this->update([

'entryable' => tap($entryable)->saveOrFail(),

]);

return $this;

});

}

}

class Edit extends Model

{

protected $guarded = [];

public function entry(): BelongsTo

{

return $this->belongsTo(Entry::class);

}

public function user(): BelongsTo

{

return $this->belongsTo(User::class);

}

public function entryable(): MorphTo

{

return $this->morphTo();

}

public function setEntryableAttribute($entryable): void

{

$this->entryable()->associate($entryable);

}

public function setUserAttribute($user): void

{

if ($user) {

$this->user()->associate($user);

} else {

$this->user()->dissociate();

}

}

}

Before we update the Entry::entryable relationship to point to the current state of the Entryable, we make sure to create a new Edit record that points to the previous state of the Entryable.

Now, we can retrieve previous versions of any Entry via the edits() relationship:

// Always points to the current state...

$entry->entryable # Note{id: 123, content: ...}

// Retrieve historical edits...

$entry->edits # [Edit{entryable: Note{id: 1}}, Edit{entryable: Note{id: 2}}, ...]

This is what I mean by "the Entry model works as a pointer." Our Entry model has access to the history of every iteration of the Entryable resource it represents. This will cost us some more in terms of database storage, but it's worth it, if you need to be able to retain immutable historical information about your data.

With that being said, creating an edit record for every change to our Entryable record might be too much. If we have an "autosave" feature, for instance, every few milliseconds after a small change, it would create an entire new record. In Writebook, all changes within a 10-minute time window will update the most recent Entryable instead of creating a new one, for example. We may tweak the behavior however we want.

Conclusion

As I said, Delegated Types is one of my favorite patterns for web applications using an Active Record ORM. Hopefully, you can see how it differs from other techniques like Single-Table Inheritance and regular polymorphic relationships. I also hope you can see how it enables new ways to use Active Record ORMs: Delegated Types gives you greater hierarchies, data immutability, and historical information—all without needing you to reach for graph databases or Event Sourcing.

These techniques are not mutually exclusive. In the post Active Record, nice and blended, Jorge Manrubia shows how they use a combination of all of these patterns in HEY and Basecamp. Everything explained there also applies to Laravel applications.

I hope you enjoyed reading this post! Drop us a line on Twitter @TightenCo if you want to ask questions, share ways you use Delegated Types, or just say hi. 👋

in your inbox:

let’s talk.

Thank you!

We appreciate your interest.

We will get right back to you.